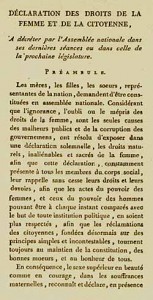

Let us therefore rectify such criminal neglect and recall her finest moment, namely: Olympe de Gouge’s authorship of the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen. There can be only one reason: she was a woman. (A proto-abolitionist, Olympe’s play – Slavery of Negroes – caused such an uproar when it was first performed in 1788 that the mayor of Paris condemned it as an incendiary act, fearing it would cause revolt in the French colonies.) Despite a multitude of groundbreaking contributions as playwright, agitator, reformer and author, Olympe’s name has until recent years been conspicuously, disturbingly, absent from historical records. But Olympe did not limit her vision solely to women’s struggles: in a flurry of political pamphlets, journal articles, and broadsides published between 17, she championed the causes of social justice and civil rights on behalf of all the disenfranchised and underprivileged: children, the poor, the unemployed and, most controversially, slaves. There is strong support for this assertion in 1791, one year before Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Woman, Olympe published the very first charter for women’s rights – which remains one of the most powerful and concise expressions of feminism. Two years before she met her grizzly fate with Madame Guillotine aged 38, Olympe wrote: “A woman has the right to mount the scaffold she must also have the right to mount the rostrum.” For a slew of similarly bold and visionary statements – radical even within that momentous milieu – Olympe has earned the distinction of “first modern feminist” among historians such as Benoîte Groult.

But that distinction, by revolutionary rights, belongs in truth to Olympe de Gouges.

Although militant feminism and female agitation were major features of the French Revolution, the woman whose name is most closely associated with this world-shattering event remains the Queen of France, Marie Antoinette.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)